Red Points’ comprehensive guide for helping brands worldwide to obtain patent protection in the United States.

Summary

In this article, we will take a look at:

- What is a utility patent and the protections it provides

- Patentable subject matter

- How to obtain a utility patent and the costs of obtaining it

- Patent term of a utility patent

- Patent infringement and defenses against it

What is a utility patent?

A patent is a grant of a property right to an inventor issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). A utility patent is a patent that protects novel, non-obvious and useful process, machine, article of manufacture, the composition of matter or improvements thereof.

While a utility patent can protect the way an article functions and/or method of using the article, in contrast, a design patent only protects the ornamental appearance for an article, such as its shape, configuration or surface ornamentation applied to an article.

A utility patent gives the patent owner “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States.” 35 U.S. Code § 154 (a) (1).

What can be patented?

According to 35 U.S.C. § 101, to be patent eligible, first, the claimed invention must belong to at least one of the four categories: processes, machines, articles of manufacture and compositions of matter.

The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP), which is published by the USPTO, in § 2106.03, provides useful definitions for each of the four patent eligible categories:

- A process, which is synonymous with method, is an invention that is claimed as an act or step, or a series of acts or steps.

- A machine is a “concrete thing, consisting of parts, or of certain devices and combination of devices.” Digitech Image Techs., LLC v. Elecs. for Imaging, Inc., 758 F.3d 1344, 1348-49 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

- An article of manufacture is “a tangible article that is given a new form, quality, property, or combination through man-made or artificial means.” Digitech, 758 F.3d at 1349. Articles of manufacture also include “the parts of a machine considered separately from the machine itself.” Samsung Electronics Co. v. Apple Inc., 137 S. Ct. 429, 435 (2016).

- A composition of matter is a “combination of two or more substances and includes all composite articles,” “whether they be the results of chemical union or of mechanical mixture, or whether they be gases, fluids, powders or solids.” Digitech, 758 F.3d at 1348-49; Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303, 308 (1980).

Second, the claimed invention should not be directed to a judicial exception, such as an abstract idea, law of nature or a natural phenomenon, unless the claimed invention, as a whole, amounts to significantly more than the exception.

The Supreme Court has stated that granting patents to inventions primarily directed to these exceptions would impede innovation rather than promote it because these exceptions “are the basic tools of scientific and technological work.” See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2354 (2014); Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 71 (2012). See also MPEP § 2106 for a detailed discussion of the judicial exceptions.

The following flow chart provided by USPTO, and reproduced from MPEP § 2106 III, provides a quick overview of the steps involved in determining what can be patented, as discussed above:

Finally, in order to be patent eligible, the claimed invention must also be useful, that is, have a specific, substantial and credible utility. See MPEP § 2107 for a detailed discussion of the utility requirement.

How to patent an idea

A mere idea or suggestion is not patentable; only inventions can be patented. An easy way to distinguish mere ideas from inventions is to ask whether the enablement requirement of patentability is fulfilled, that is, can a person of ordinary skill in the art make and use the innovative concept without engaging in undue experimentation? A mere idea or suggestion would not be enabling to one of ordinary skills in the art.

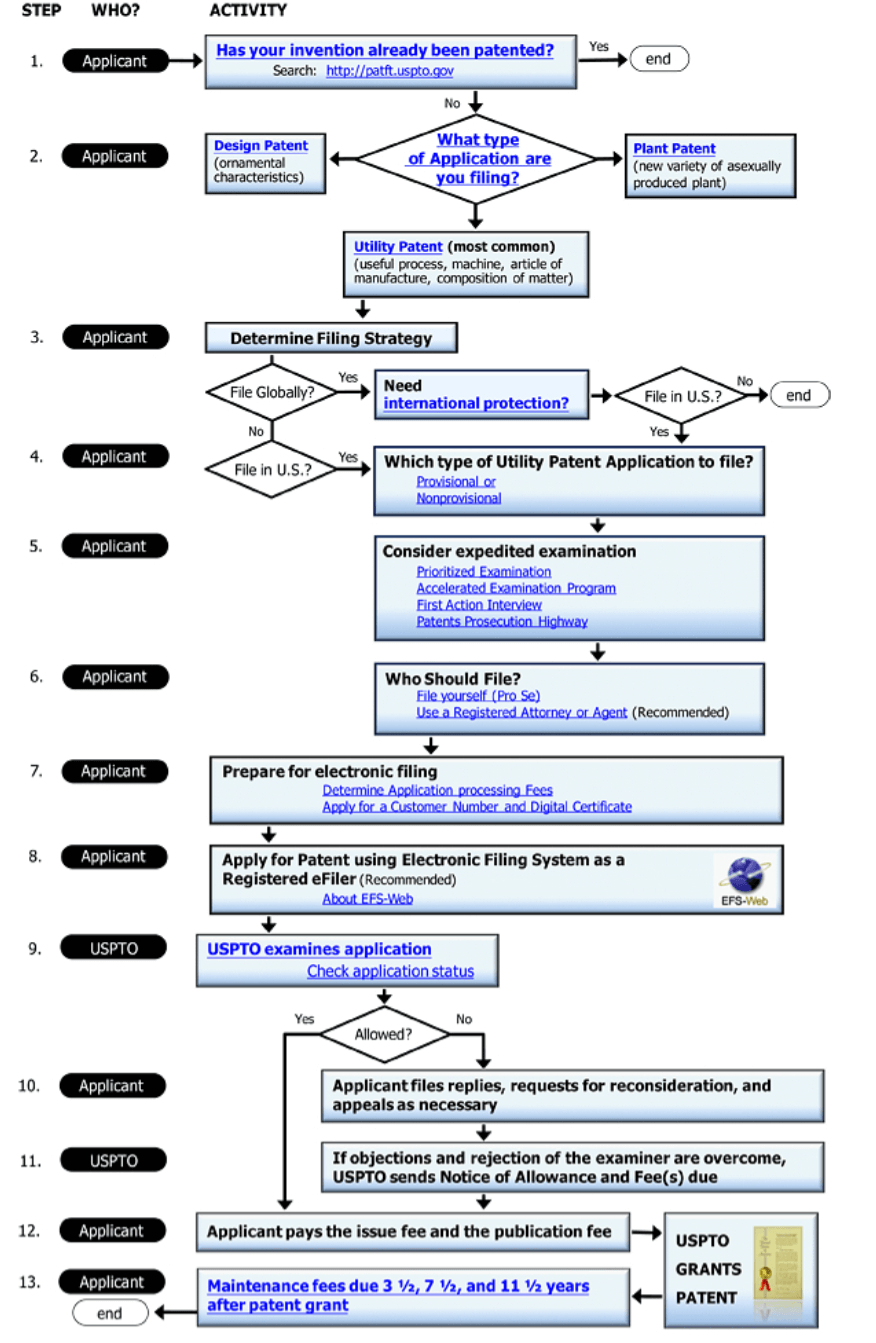

How to get a utility patent

To get a utility patent, the applicant must ensure that the claimed subject matter of their invention:

- is patent eligible: Under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the claimed subject matter must be a process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter and not directed to a judicial exception, as described above;

- is useful: have a specific, substantial and credible utility. MPEP § 2107;

- is novel: Under 35 U.S. Code § 102, a claim is novel unless “each and every element as set forth in the claim is found, either expressly or inherently described, in a single prior art reference;”

- is non-obvious: Under 35 U.S. Code § 103, the claimed invention is non-obvious unless “the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art;” and

- fulfills the written description requirement (the patent application shows that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention at the time the application was filed) and the enablement requirement (a person of ordinary skill in the art can make and use the invention without engaging in undue experimentation) under 35 U.S. Code § 112.

Prior to filing a patent application with the USPTO, it is advisable that applicants at least perform a preliminary patentability search using the USPTO patent database to search for previously filed U.S. patent applications similar to their inventions for assessing novelty and non-obviousness.

The applicants may choose to widen the scope of their search and use global patent databases such as PatentScope or Google Patents, which searches foreign patent applications and international applications in addition to the U.S. patent database. Applicants may even use search engines such as Google or Google Scholar to identify any similar prior art that are not patent applications.

On the other hand, the downside of performing an extensive search is that the applicant would need to disclose any relevant prior art identified to the USPTO. Therefore, some applicants may prefer to do a more preliminary search prior to filing the utility patent application.

How much does a utility patent cost?

The cost of obtaining a utility patent is highly variable because it depends on variables such as complexity of the application, attorney and paralegal fees, number of claims in the application, number of pages in the application, extensions of time obtained at the USPTO for responding to Office Actions during prosecution, etc.

The USPTO fees are lower for small and micro-entities. See 37 C.F.R. § 1.27 and 37 C.F.R. § 1.29 for definitions of small and micro entities, respectively. A list of the USPTO patent filing, search, examination, and post-allowance fees can be found here.

Provisional patent applications

If the costs of filing and prosecuting a standard utility patent application, also known as a non-provisional patent application, seems prohibitive and the inventors would like to do further work before deciding whether or not to pursue a patent, a good option is to file a provisional patent application.

A provisional application gives the applicant the benefit of an earlier priority date and the option to decide whether or not to file a non-provisional application a year from the date of filing of the provisional application.

One year after the provisional patent application is filed, the applicant must file a non-provisional patent application, otherwise, the application would go abandoned. Unlike a non-provisional application, a provisional application does not need to comply with the patentability requirements described above, or even have any claims, because a provisional application is never examined.

However, if the applicant decides to file a non-provisional application claiming priority to the provisional application, the provisional application must provide adequate written description and enablement for the claims in the non-provisional application to avail the benefit of the earlier priority date. Therefore, the best practice is to file a provisional application that complies with all the patentability requirements outlined above.

How long does a utility patent last?

If the utility patent does not claim priority to an earlier-filed application, the patent term of a utility patent is twenty years from the date the application for the utility patent was filed in the United States.

If the utility patent claims priority to earlier-filed U.S. non-provisional application or an international application, the patent term for such a utility patent is twenty years from the date of filing of the earlier-filed U.S. non-provisional application or international application.

It is important to note that if a utility patent claims priority to a U.S. provisional application, the patent term of the utility patent is still twenty years from the date the non-provisional application for the utility patent was filed in the U.S., not twenty years from the date of filing of the provisional application.

Additional patent term may also be granted as patent term extension or patent term adjustment for delays caused during patent examination at the USPTO or regulatory delays caused by agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). See MPEP §§§ 2710, 2733 and 2750 for a detailed discussion of patent term extension and patent term adjustment.

What is patent infringement?

To successfully sue for patent infringement, a patent owner would have to show in court that the other party is making, using, offering to sell, or selling the patented invention in the U.S., or importing into the U.S. any patented invention during its patent term without authority.

Patent infringement is determined on a claim-by-claim basis, that is, the patent owner only needs to show that each and every element of a patent claim is present literally or equivalently in the accused party’s product or method. A showing of infringement does not require a showing that all claims in the patent are being infringed.

The following are some defenses to patent infringement that the accused party can present:

- Non-infringement: The accused party can argue that the patent owner has failed to show that their activities infringe upon the patent owner’s patent by poking holes in the infringement case, such as showing that not each and every element of the patented claim is found in the accused’s product.

- Patent invalidity: The accused party can succeed by showing that the granted patent claim is invalid because it does not satisfy any of the five patentability requirements discussed above (Patentable Subject Matter, Utility, Novelty, Non-obviousness, Written description, and Enablement) under a clear and convincing evidence standard.

- Experimental use: Under common law, the experimental use defense can be argued if the accused party was using the invention for amusement, to satisfy idle curiosity, or for strictly philosophical inquiry. This defense cannot be argued if the use is even remotely commercial in nature.

- Safe-harbor rule: Under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1), if the accused party can show that the infringing activities are “reasonably related to the development and submission of information” for the FDA, then these activities cannot be deemed as infringing.

- Inequitable conduct: If the accused party can show that the patent owner or their representative engaged in inequitable conduct under a clear and convincing evidence standard, then the entire patent, not just the claims allegedly being infringed, will be invalidated. The accused would need to show that

1) the patent owner or their representative failed to disclose material information to the USPTO such as prior art, or

2) that they submitted materially false information to the USPTO, or

3) that they made affirmative misrepresentation of material information to the USPTO, and

4) that the patent owner or their representative intended to deceive the USPTO.