Torrenting and internet piracy may be making a comeback – Red Points investigates the new research on patterns of global internet usage.

- The growth of legal streaming services largely “killed” torrenting

- Research from 2018 has shown a resurgence in levels of torrenting

- Platform-exclusivity deals and global wealth inequality are blamed for this return

What is torrenting?

Torrenting is a form of file sharing used between internet users. It’s a form of sharing files that isn’t too costly on one key user, hosting the document. This method of peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) relies on a group of users, known as seeders, who already have the files on on their devices, sending the files to those who want to download the file, called leechers.

To do this, the song, or movie, or software is broken up into tiny parts, known as packets, and each seeder sends their share of the file bit by bit. Once a leecher has received the entire file, the download is complete, and the torrenting software will then list them as a seeder, to automatically re-distribute the file to any new leechers. This method is has proved to be success as the shared hosting or seeding “cost” means the more popular an file is, the easier it is to download and seed.

Sites like The Pirate Bay and Kickass Torrents do not host the content people are downloading; they act more as a directory and host “magnet links”. These links are used by torrenting programs like uTorrent and BitTorrent to find other torrent-users who are seeding the file.

So instead of a single user or content-hosting website sending a movie in its entirety to a person, which could take a long time, many people with the file on their computer each send a small part of it at the same time, greatly reducing both the time it takes to send the movie and the odds of a failure in the download.

The more popular a file is, the more people are likely to be seeding it, and the quicker it can be sent. A brand new superhero movie or an episode from a popular TV show are likely to have tens of thousands of seeders on certain platforms, which would take someone with a strong internet connection only moments to download. A recording of a 40 minute clarinet solo played in a small jazz bar in the 1960s would be lucky to have even 1 or 2 seeders.

Torrenting is not inherently illegal. The aspect of criminality is only added to torrenting when the files being exchanged are copyright-protected, or are otherwise illegal, such as with banned books.

What happened to torrents?

2006 was truly the last great moment of P2P file sharing; so much so that earlier that year, 70% of all internet traffic was attributed to it. Only months later, YouTube and other web traffic had overtaken P2P. By 2011, P2P was down to 19% of internet traffic, and fell again to 7% in 2013.

The growth of streaming services starting in 2006 was so fast and culturally important that it Time Magazine made “You”, referring to both YouTube and the internet community in general, as 2006’s Person of the Year. But YouTube wasn’t alone in their influence against P2P traffic.

2010 saw Netflix pivot massively from shipping physical DVDs to consumers through mail to focusing on their online streaming services. Within months, they become North America’s largest source of evening streaming traffic. By the middle of 2011, their subscriber count was as 23 million in the US alone. Netflix had, in essence, solved the problem that people faced with the multitude of divided television channels and packages. By offering all their customers’ favourite tv shows and movies in one place, viewers could use a single subscription and get all the premium video content they desired.

In 2011, file sharing still had some life left, especially on fixed networks. The majority of upstream traffic in the USA the EU was still being attributed to torrenting, however this wasn’t going to last long. By 2015 upstream file sharing was down to 27% and 21% respectively as both legal and illegal streaming options had firmly taken centre stage and internet users had massively diversified their use of the internet, with the continued growth of social media, egaming and OTT messaging.

Are torrents coming back?

However, it seems that the analysts claiming the death of torrenting had arrived may have spoken too soon. Research from Sandvine, released earlier this month, shows a marked increase in torrenting in a number of regions.

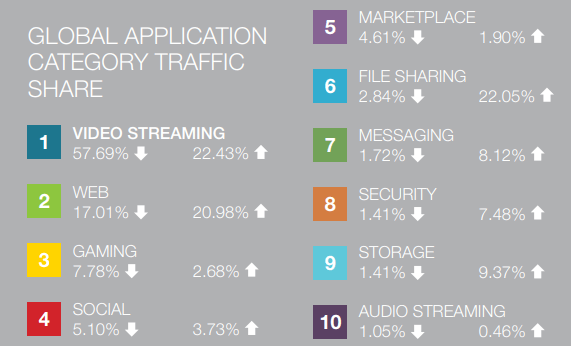

Netflix remains a giant in terms of internet traffic, representing 15% of the total global downstream volume traffic alone. Video streaming in general has become a “bandwidth hog”, in total accounting for 58% of all downstream internet traffic.

Conversely, file-sharing makes up only 3% of downstream traffic, but makes up a considerable upstream volume at 22% of all traffic, a number which rises to nearly one-third in Europe, the Middle-East and Africa. BitTorrent was especially highlighted as seeing a resurgence; 97% of the aforementioned upstream traffic from file sharing goes to BitTorrent, clearly establishing it as the dominant force in P2P. BitTorrent can be viewed as a sort of canary in the coalmine for piracy – the success of the communication protocol is used as an indicator for the level of global content piracy in general.

BitTorrent’s recent growth could also be attributed to uTorrent Web. After being available for the past few years as a beta program, uTorrent Web was released as a stable version in early September, and within a month had reached one million active monthly users. The program allows users to stream and download torrents through their browsers, rather than from a standalone program, making the P2P sharing experience even smoother for users.

The Sandvine report also identifies file-sharing site Openload as the 8th biggest site in terms of downstream traffic. This represents just 0.8% of overall downstream traffic, but that number jumps 3.7% in the Asia Pacific region and down to 0.39% in the Americas. The site has now been listed on the US Trade Representative “list of notorious markets”, though Openload denies accusations of being a piracy site, defending their legitimacy with their DMCA-compatible policies.

So, what’s the cause for this renewed interest in torrenting? The biggest factor is likely to be the current excess of platform-exclusivity streaming options. As stated, a huge part of Netflix’s success is attributed to their ability to provide customers with all the content they wanted. However, recent years have seen a reversal of this. Streaming services like Netflix, HBO Go, Hulu and Amazon Prime now each offer shows exclusive to their services, like House of Cards, Game of Thrones, The Handmaid’s Tale and Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan respectively. In short, viewers seem happy to pay for one or two streaming services, and then pirate content unavailable on their subscription channels.

There are also the problems related to the geography of viewers. When episodes are released for shows that are particularly hyped, and certain groups of viewers are restricted from seeing the episode because the show is unavailable in their country, or if it’s released too long after others have seen the episode, viewers then pirate the episode. This is predominantly an attempt to avoid spoilers, as huge moments in an episode will be the talk of offices and social media alike. No one wants to be the one person who hasn’t seen “last night’s unbelievable episode”, so they get their hands on the episode however they can.

There’s also an argument to be made that modern content ownership laws are also driving consumers back to piracy. The ability for content providers such as Apple and Amazon to remove books and movies from users’ digital libraries due to copyright concerns has sparked ire from many consumers. Such consumers are accustomed to purchasing a book, album or hard-copy movie, and are unhappy with the idea of not fully owning their product, that the content they pay for is only rented to them at the regular retail price.

So whether this recent uptick in torrenting is simply the death throes of mass online piracy, or is the start of a significant return to the patterns of the early 2000s, remains to be seen.

Developing nations boosting piracy

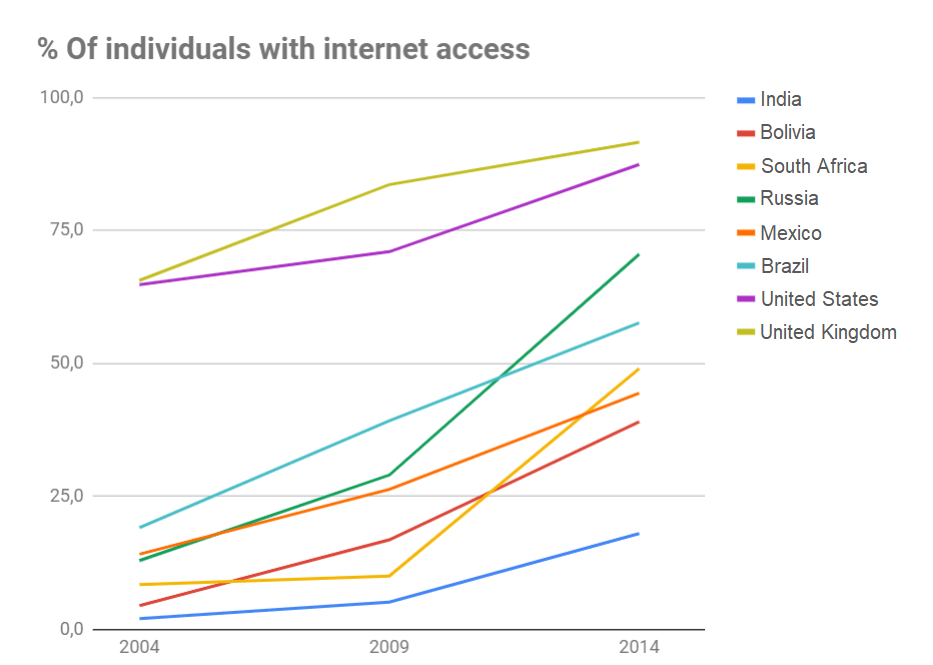

The final argument to be made for this slight return to torrenting is the effect that developing nations are having. As seen in the graph below, nations across the world have been gaining internet access over the years. Some, like South Africa and Russia have seen dramatic improvements over the past decades, others like Brazil and Mexico have seen steadier growth.

However, the problem is that, as many countries approach the internet ubiquity enjoyed in countries in northern Europe or the United States, they are now experiencing the same “growing pains” surrounding piracy. The problem is especially compounded with the stark difference in the wealth of some of these nations. Paying for a download of a movie or an album for $10-$20 is considerably easier for someone in the United States than for the average person in India, based on average incomes. The difficulty for entertainment companies is the fear that lowering prices to fairer levels in lower-income countries could result in end users possibly reselling those subscriptions back to users in rich countries at prices massively under regular retail prices.

This is especially true for software piracy, which is experiencing noticeably high levels of illegal downloads and file sharing in poorer areas of the world. Trade representatives from rich countries demand poor countries tighten their intellectual property laws, but when the real-world cost for software is eight times higher for people in poor countries than in rich countries, and that software is essential for businesses across the world to stay competitive in a globalised internet age, the reasons for widespread software piracy in circumstances such as these become extremely apparent.