China’s appetite for consumer goods and western brands is growing. Alibaba, China’s largest online retail group, has been on a mission to entice big brands to their sites in recent years.

China’s booming middle class want more diversity and more foreign brands. Many western businesses have been eager to tap into such a large market, and many media outlets have put a lot of focus on the endless opportunities that China provides, but few mention the complexities. Conducting business overseas is nearly always fraught with problems and China, far from being the exception, can be particularly challenging.

This series of articles focuses on the essential elements of selling in China and how to avoid problems that could cost businesses profits, time and even rights ownerships. Through discussions with our legal team and other professionals, we have compiled this introductory advice for medium-sized organisations who want to begin operations in China.

How intellectual property in China works

We start with one of the most important aspects of working in China, intellectual property rights (IPR). It is well known to be one of the most important aspects to consider before beginning operations in China. IPR protection should be a priority for any business with a presence online or in China.

In recent years, the global trade in counterfeit goods has been estimated to be worth around half a trillion dollars, or 2.5% of world imports, 84.5% of which originate in China and Hong Kong. In Chinese Shanzhai culture, essentially copying products, is such that there will always be a market ready to purchase replica or fake version of brands.

Sadly, issues with IP ownership, copies, or brand abuse are typical problems for brands selling in China. Dan Harris, a prominent expert in Chinese law, says “If you only do one thing, register your trademark in China”. Without a registered trademark, there is little that companies or legal entities can do to prevent counterfeiting and protect your business interests. While it is also important to register and protect patents and designs, in this section, we will be focusing on trademarks as it is the element of IP that affects every sector.

China’s IP Framework

The EU and China have a similar IPR legal framework, and China is always seeking to operate in conjunction with other countries. China has signed up to numerous international bodies and agreements such as:

» WIPO

» WTO

» Paris Convention

» Berne Convention

» Madrid Protocol

» Patent Cooperation Treaty

These are designed to create a fair business environment for IPR holders. These conventions help standardise the laws across borders to a degree. China is a member of these conventions, so there are some basic underlying principles of IP law that work in both Europe and China.

However, it’s important to remember that the procedures and practice of Law in China are different from the EU, and businesses should not expect that IPR registration or enforcement will be carried out in the same way as in their home countries. Cultural and language barriers are always significant roadblocks for outsiders doing business in China.

There are unwritten rules and cultural norms to consider when forging business partnerships or seeking to enforce IPR, so it’s always recommended to use a Chinese law firm or use a legal service that specialises in Chinese IP law.

Trademarks in China

Brand identity is the key to success in any marketplace; China is no exception. It is crucial to register your trade name, logo and service marks in China. By not doing so, another business can appropriate them easily. Chinese IP protection is important even for companies not selling in China but using the country to manufacture goods, in order to secure rights.

REGISTRATION

The Chinese Trademark Office (CTMO) receives over one million applications a year, and it is almost impossible to conduct business in China without an extensive portfolio of both Chinese and English language “word-marks” and logos. Also, you must register for China / Hong Kong / Taiwan / Macau correctly. When registering a trademark in China, there are a few different options.

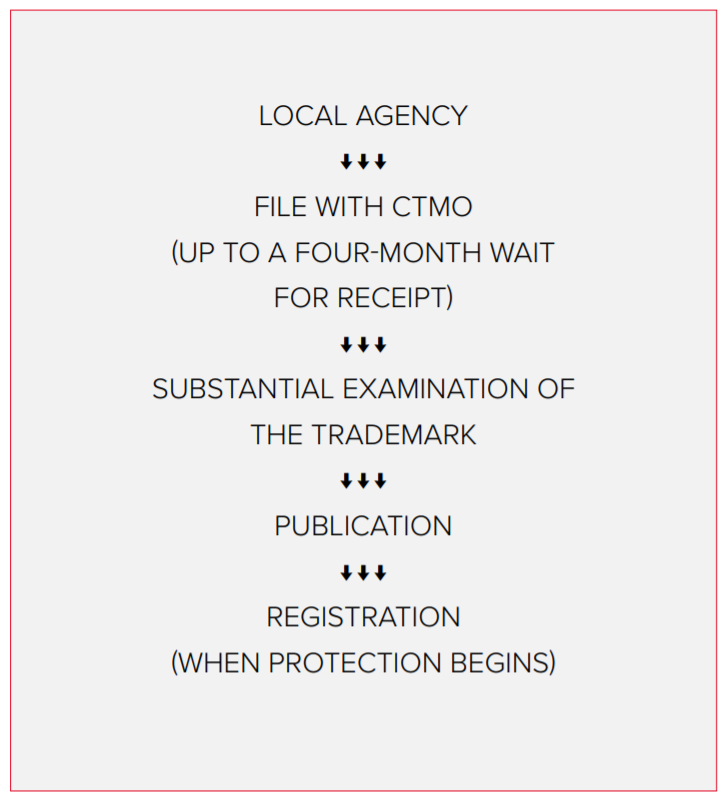

NATIONAL TRADEMARK

Businesses go directly to the CTMO using a Chinese agent, filing an application in Chinese and the result is a Chinese registration certificate. If a business has a registered Chinese address then it is possible to file a national trademark with the CTMO, however generally it is advised to use an in-country agency or a firm that specialises in Chinese law. The national filing system usually follows this procedure:

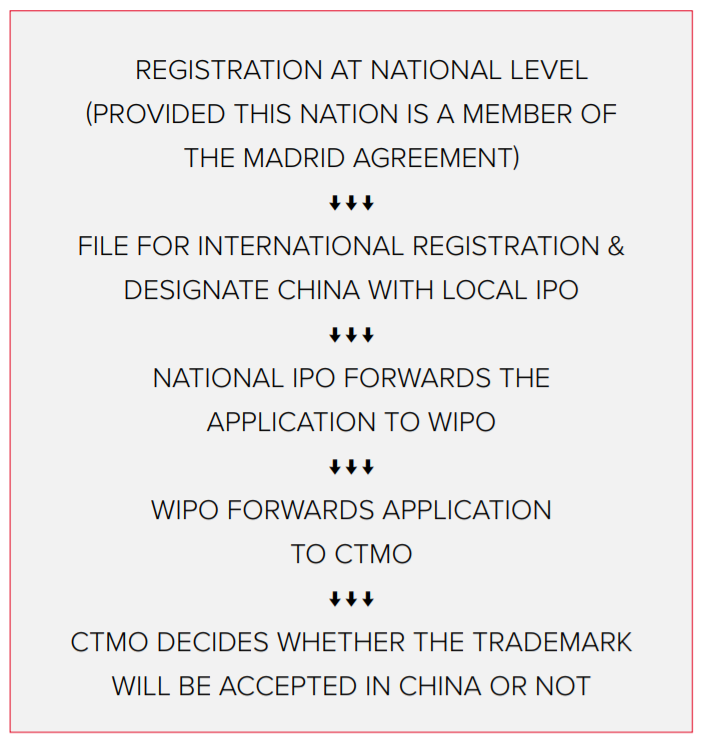

INTERNATIONAL TRADEMARK

When you want this extended to China, you will need to request this “confirmation certificate” from the CTMO. This certificate is simply details about your trademark, such as the owner and other fundamental aspects. It is simply for Chinese officials to have some information authenticated and in Chinese, that they can easily access and understand. If the company doesn’t have a registered Chinese office, then they will have to go through a Chinese agent. The structure is as follows:

Legal protection in China starts from the registration date. It is important to do this as soon as possible, as the application date will not be considered under protection and the registration process is not fast.

Another reason to register your trademark quickly is that China uses a “first to file principle”. This is important as in some parts of the world there is an element of protection for companies on the grounds of prior use elsewhere, but this is not the case in China. Some previous-use protection does exist, however it is tough to access and is not given to every company who seeks it.

For international trademarks that have been extended to China, businesses must first obtain the “confirmation certificate” before their legal protection begins in China. Again, the first to file principle is extended to international trademarks.

DURATION

In the event that a trademark has not been used for three years from the Chinese registration date, then this trademark is effectively cancelled. This differs from most European trademarks which provide five years of coverage. An active trademark is similar to European regulations; it is active for ten years and can be renewed indefinitely.

TRADEMARK USE

Under Chinese law, trademarks must be used exactly in the way that they have been registered. For example, if Quiksilver were to register their brand using the logo and the text beneath it then this is how it must appear. The text “Quiksilver” that doesn’t appear with the logo would not be considered protected; the same applies to cases where the logo appears without the text.

This means that in cases where the registered trademark, with both text and logo, is never used with the two elements together, someone can file a cancellation request as this trademark is not in use.

This also means that companies must build strong trademark catalogues by registering all the variations of the logo and text.

CHINESE LANGUAGE REGISTRATION

An English-language brand that becomes popular in China will often gain a Chinese name. Generally, it is better to be ahead of the curve and provide your brand with a Chinese name when operating in China. Word marks or logos written in the Roman alphabet do not guarantee anything.

To ensure you have control of your trademark it is better to either translate your brand name directly into Chinese or create a phonetic translation, so the word sounds similar. These should feature in written Chinese with the logo and also be registered to avoid trademark squatting in Chinese.

A good example of the potential consequences of not registering your trademark in Chinese is the basketball star Michael Jordan. Michael Jordan’s name in Chinese is commonly transliterated to 乔丹, or Qiaodan. A now large Chinese company called Qiaodan Sports is allegedly using 78 of his trademarks, including his name. The case has gone on for years, and Mr. Jordan continues to lose.

The takeaway from this is always to register your trademark in Chinese or someone else will. In more extreme cases, failure to cover a Chinese trademark can result in a lawsuit. New Balance was forced to pay half of their profits from 2011 to 2013 ($15.8 million) to an individual who had registered the Chinese transliteration of their brand, Xin Bai Lun, which New Balance used on some adverts and websites.

NICE CLASSIFICATION

The Nice Classification is the international classification of goods and services applied to trademarks. China uses a translated version of this system. It’s important to list every single classification of good or service to be protected by the trademark, ensuring that these correspond exactly to the Chinese translation of the classification. You also need to register the class and the sub-class of each product.

For example, protecting your product under the class of clothing and subclass of a dress does not extend to wedding dresses as this is a different class of product. There is also the issue that the CTMO is likely to reject trademark applications if there is a match with a similar brand in the same classification.

For example, if “Steady” is a registered trademark in the classification of “tools” within the construction class, it is unlikely that they will pass a trademark for “Steady Painting and Varnish” within the same class without a clear subclass difference. An advantage of registering your brand at Chinese level and not through the Madrid system is that you are able to decide which subclass your trademark is registered in. When registering through the Madrid system, it is the decision of the CTMO official which subclasses your trademark will be covered by. This can lead to over-classification, meaning a higher chance of the application being rejected, or under, where your trademark doesn’t provide sufficient protection.

Generally speaking, it is better to cover as many sub-classes as possible to prevent other companies trading under your name in a different class of product.

The contents of this blog come from our free downloadable ebook, How To Sell In China